Self-repair of bones: a new approach to restoring cranial bones without the use of bone tissue implantation

In a groundbreaking study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers from the University of Pittsburgh have discovered a new approach to bone regeneration in adult mice without the need for biomaterials or implantation of bone tissue. Using a device similar to an orthodontic wire, the researchers carefully stretched the skulls of mice along their sutures, activating skeletal stem cells in the seams. This technique successfully repaired damage to the skull that would not have healed on its own. The team believes that this approach could be used to develop novel therapies for people.

The study was inspired by babies, who have an exceptional ability to regenerate bone defects in the calvarial bones that form the top of the skull. The bones in babies are not completely fused, which means that the sutures where stem cells reside are still open.

Baby skull

The researchers hypothesized that by mechanically opening the sutures in adults, they could activate the stem cell niche and boost stem cell numbers to promote bone regeneration.

Research methodology:

The researchers used a bone distraction device to apply a controlled pulling force to the calvarial bones of mice. This force was strong enough to slightly widen the sutures without causing a fracture. Using single-cell RNA sequencing and live-imaging microscopy, they found that the number of stem cells in the expanded sutures of these animals quadrupled. As a result, mice treated with the device regenerated bone to heal a large defect in the skull.

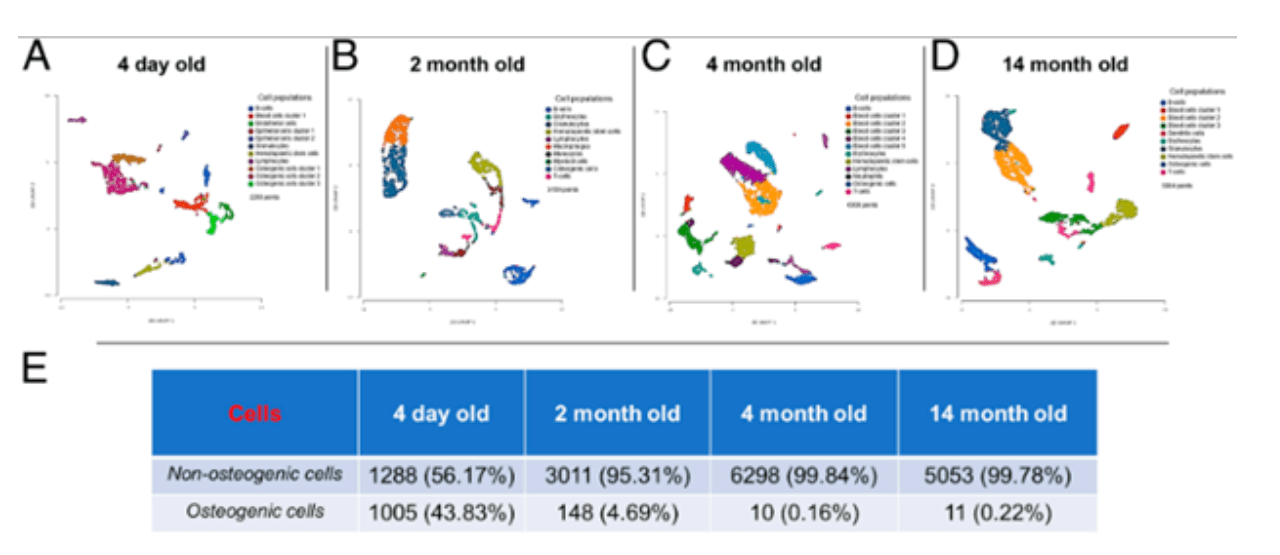

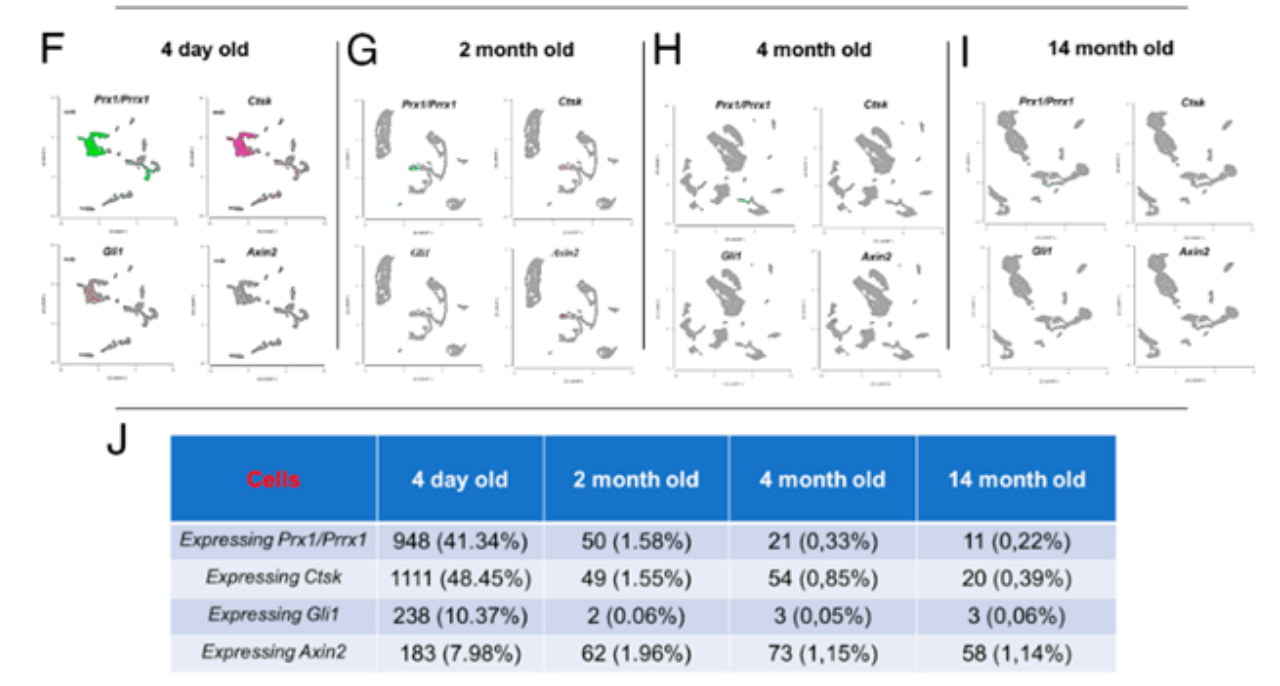

Single cell RNA-sequencing analysis of 4-d-old, 2-mo-old, 4-mo-old, and 14-mo-old calvarial sutures. (A–D) Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) plot showing unbiased graph-based clusters distribution of all cell populations in sutures isolated from 4-d-old (A), 2-mo-old (B), 4-mo-old (C), and 14-mo-old (D) mice. (E) Quantification of osteogenic and non-osteogenic cell lineages (absolute numbers counted in each sample and percentages of the total cells within each sample). (F–I) UMAPs displaying the expression of Prx1/Prrx1, Ctsk, Gli1, and Axin2 in calvarial sutures of 4-d-old (F), 2-mo-old (G), 4-mo-old (H), and 14-mo-old (I) mice. (J) Quantification of cells expressing Prx1/Prrx1, Ctsk, Gli1, and Axin2 (absolute numbers counted in each sample and percentages of the total cells within each sample). 4-d-old mice: total cells 2,293 (n = 8); 2-mo-old mice: total cells 3,159 (n = 5); 4-mo-old mice: total cells 6,308 (n = 5); 14-mo-old mice; total cells 5,064 (n = 6).

While the approach was effective in healing skeletally mature 2-month-old mice, it did not work in 10-month-old, or middle-aged, rodents. This is because the quantity of stem cells in calvarial sutures is very low in older mice, so expanding this niche is not as effective in boosting healing capacity.

“Our approach is inspired by babies because they have an amazing ability to regenerate bone defects in the calvarial bones that make up the top of the skull,” said senior author Giuseppe Intini, D.D.S., Ph.D., associate professor of periodontics and preventive dentistry at the Pitt School of Dental Medicine, member of the McGowan Institute for Regenerative Medicine and an investigator at UPMC Hillman Cancer Center. “By harnessing the body’s own healing capacity with autotherapies, we can stimulate bone to heal itself. We hope to build on this research in the future to develop novel therapies for people.”

The full version of the study can be read in the article published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences journal.

Current treatments for damage to the skull involve bone grafts or implantation of biomaterials that act as scaffolds for bone regeneration, but these approaches are not always effective and come with risks. The researchers are investigating how their findings could be used to inform novel therapies in people, not just to heal skull injuries but also fractures in long bones such as the femur.

Bone distraction devices are already used to treat certain conditions such as a birth defect called craniosynostosis, in which the calvarial bones fuse too early. Expanding this technique to promote bone regeneration could be a future focus of clinical trials. The team is also investigating non-mechanical approaches to activate skeletal stem cells such as medications. This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research.