Screw vs. Cement Fixation of Crowns on Implants: Part 1

In this article, we aim to determine if screw fixation of prostheses holds an absolute advantage over cement fixation. Our discussion will focus solely on practical considerations, drawing upon research findings and analyses of specific clinical cases. It is important to note that no system possesses an unconditional superiority. We also wish to assure the staunch advocates of either system that both fixation methods are commendable and can lead to high-quality restorations with favorable long-term outcomes. Although the prevalence of screw fixation is on the rise due to the advancement of CAD/CAM technologies and the fabrication of prostheses from monolithic zirconia, we should examine the evidence methodically.

When is it permissible to use only screw fixation of prostheses?

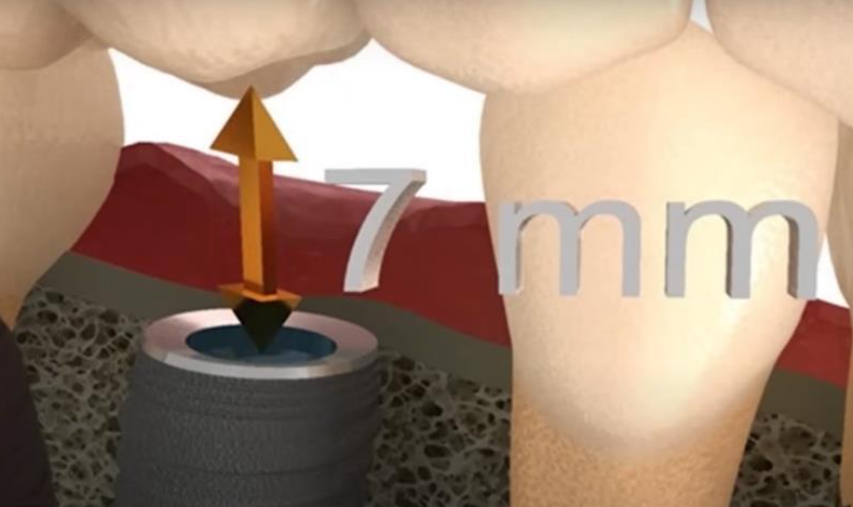

- A clear indication to opt for a screw-retained restoration arises when the interocclusal distance from the implant platform to the opposing cusp is less than or equal to 7 millimeters. In such cases, cement fixation becomes physically unfeasible.

The critical distance from the base of the implant to the antagonist tooth at which only screw fixation should be used

The rationale behind this is that for a dependable cement fixation, the abutment height should be approximately 5 millimeters, while the occlusal thickness of the prosthetic material should be around 2 millimeters, which is notably minimal. Whether the restoration is metal-ceramic or zirconia-based, fabricating an abutment and crown within such constraints is nearly unattainable.

The principles outlined here are well-documented in numerous textbooks and have been established as irrefutable standards for many years.

- Screw-retained restorations are considered conditionally removable structures and are typically utilized when frequent removal of the prosthesis is necessary. The prosthesis is secured to the abutment with screws, and the screw access holes are sealed with a composite material. This allows for easy removal of the prosthesis by unsealing and unscrewing the shaft if needed. This feature is particularly beneficial when a temporary prosthesis is initially placed, with the intention of replacing it with a permanent one after several months. While temporary cements are available for cement-retained restorations, there are instances where the prosthesis may become prematurely uncemented or, conversely, it may be impossible to remove the crown without causing damage.

What is the essence and simplicity of cement fixation of prostheses?

It may appear that screw fixation is a recent innovation, yet it has been a staple in implantology since the inception of implants. Screw fixation was predominantly employed even with the earliest Brånemark System implants. Although these systems differed from contemporary ones, the principle remains the same. Cement fixation later gained popularity as it offered a more convenient workflow for orthopedic surgeons.

Given that an implant serves as an artificial root and an abutment acts as a tooth stump, it is relatively straightforward for a dental technician to fabricate abutments and create crowns or bridges. Similarly, it is simple for a dentist to secure the prosthesis with cement. Moreover, the cement allows for the compensation of minor fabrication inaccuracies in the prosthesis, facilitating its installation.

Both methods have coexisted harmoniously for an extended period. However, debates have emerged regarding which type of fixation is more reliable over the long term.

Which type of fixation is more reliable in the long term?

There are staunch advocates for screw fixation alone, as well as exclusive proponents of cement fixation. The debate reached a point where, in 2009, Dr. Salvi and a team from the University of Bern did a special review for an ITI consensus conference.

Dr. Salvi’s group concluded the following:

“There was no evidence of increased mechanical or technical risks for fixed prostheses after reviewing three out of four studies (one prospective, one retrospective, and one sequential study) comparing screw-retained versus cement-retained fixations.”

In other words, the group observed no significant differences in terms of prosthesis survival or complications.

Adding a touch of humor, in response to the question, “Who are better, skiers or snowboarders?” the answer would be – both have their merits. It’s important to recall that during the period in question, metal-ceramic restorations were prevalent, whereas now, the use of zirconia is on the rise. Despite the new material not influencing the complication risk, screw fixation has become more favorable and straightforward, particularly with the enhanced precision of prosthesis production via CAD/CAM technologies, benefiting both the specialist and the patient.

How the debate between cement and screw fixation methods began

The emergence of this debate can be traced back to the proliferation of dental implants in the market, which was accompanied by the immediate availability of standard superstructure components, particularly abutments in various configurations.

Pre-fabricated abutments for implants with an internal hexagon interface include, from left to right: a straight abutment for cement fixation; an angled abutment for cement fixation; an angled abutment with an anatomical margin for cement fixation along the gum line; and an angled multi-unit abutment for screw fixation.

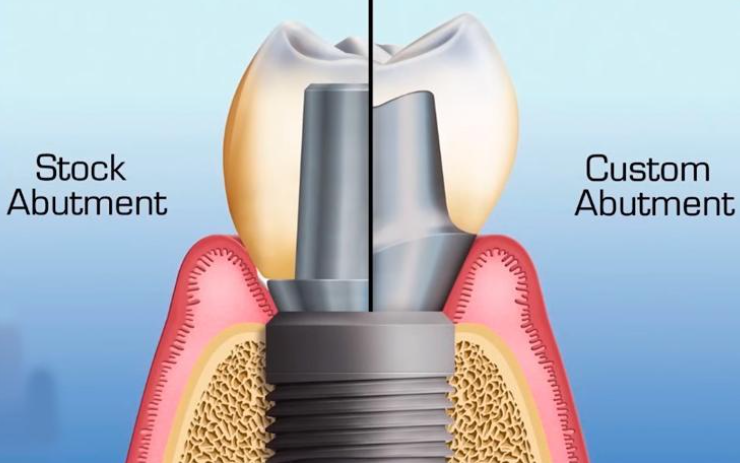

The implant restoration process is standardized. The implant serves as a root prosthesis, and the abutment installed within it acts as a tooth stump, upon which the dental technician fabricates a crown, whether it be a single unit, a bridge, or a complete denture. Historically, stock factory abutments were the norm, modified by dental technicians to suit the specific prosthesis type. However, by the mid-1990s, technological advancements enabled the production of custom abutments tailored to the patient’s gingival contour.

It’s evident that stock abutments are sufficiently effective and cost-efficient due to large-scale production. They are manufactured in the same facilities as the implants, ensuring perfect compatibility of interfaces.

A dental technician takes a stock abutment, adjusts its height as necessary, shapes a rudimentary profile, then models a metal-ceramic crown, and forwards the assembly to the clinic. Upon receipt, the dentist secures the abutment with screws and affixes the crown using cement. This straightforward method is still widely employed by many professionals.

However, the process is not always so simple. For instance, consider an older restoration where a flat interface (external hexagon) was utilized, and a single crown was cemented onto a standard abutment.

This scenario was commonplace and generally yielded satisfactory outcomes.

But look at the standard abutment, which “submerged” into the patient’s gingival sulcus.

The thickness of the patient’s gums is too large for this type of abutment – placing a cement-retained crown in such conditions is not recommended

Crucially, it cannot be claimed that the technician erred in this situation. The abutment’s neck was of a standard design, leaving no room for alteration.

Gum thickness varies among patients. If the gum were thinner than the abutment’s neck, a technician would likely reduce the neck with a bur. Conversely, if the crown’s margin is deep under the gum, it poses challenges, as the dentist may struggle to remove excess cement effectively.

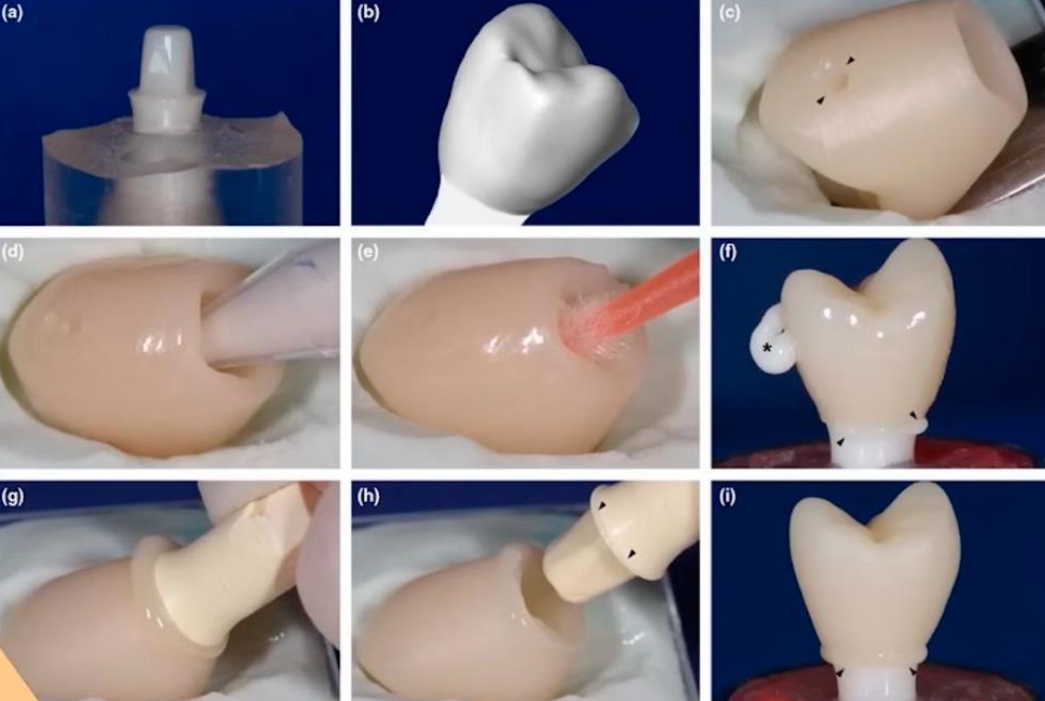

This led to alternative techniques to prevent cement from entering the peri-implant space. For instance, an abutment duplicate is created using silicone or composite.

Cement is applied to the duplicate, inserted into the crown, and then the duplicate is removed, leaving the crown with cement to be placed on the patient’s abutment.

This process must be executed swiftly: the duplicate is removed, excess cement is cleared, and the crown is positioned in the mouth. This technique is believed to minimize excess cement contact with the soft tissue at the gingival margin. While effective for single crowns, it becomes impractical for complex prostheses with multiple crowns.

And most importantly, this does not provide a 100% guarantee that the cement will not extrude.

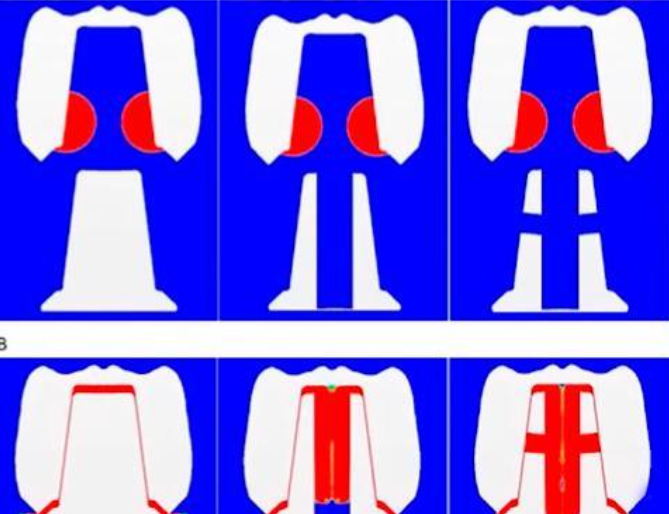

Other methods have been proposed to address this issue, as illustrated below.

The study from 2014 investigated methods to prevent cement extrusion into peri-implant tissues.

One approach involved drilling the abutments to create special ventilation channels for the excess cement, which proved to be an effective technique.

Additionally, a 2018 paper suggested creating a hole in the crown to allow excess cement to escape under pressure, offering another viable solution.

But unfortunately, practice shows that none of these methods can help if the crown margin is excessively submerged within the gingival cuff.

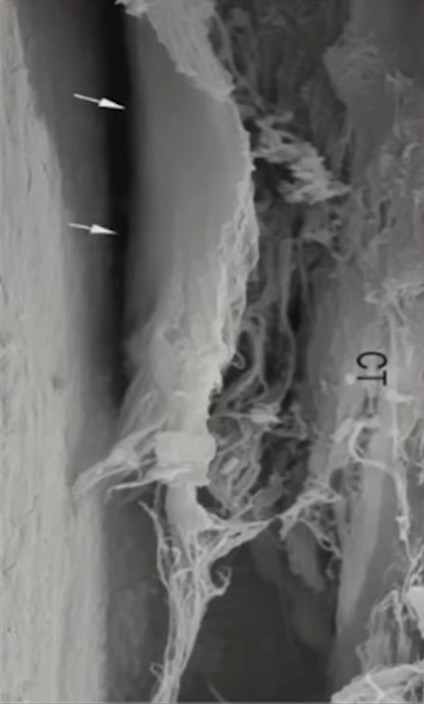

As we’ve explored in our series on soft tissue integration, the gingival cuff’s structure around a living tooth differs significantly from that around an implant. The attachment between the gum and the implant is relatively weak, which underscores the importance of ensuring the crown margin does not penetrate too deeply into the gingival tissue to avoid complications.

During crown installation, the extrusion of cement can disrupt the delicate collagen bonds and infiltrate the surrounding areas as directed by the initial placement force of the crown. The absence of a robust periodontal ligament, which is not present around an implant, means there is no barrier to halt the flow of cement.

We’ve only touched on a fraction of the methods designed to prevent cement from entering the peri-implant space. However, they share a common limitation: there is no certainty that cement extrusion can be completely avoided.

Dr. Linkevičius and his team, in their publication “Zero Bone Loss,” review numerous techniques and, despite the quality of their illustrations, they affirm that no method can entirely prevent cement penetration if the crown’s margin is excessively deep relative to the abutment base.

In cases where switching to screw fixation is not an option, two alternatives can be considered:

- Utilizing stock abutments with varying base heights to closely match the patient’s gingival thickness, thereby minimizing the depth of the crown’s margin. This approach eliminates the need for abutment drilling, creating abutment duplicates, or other complex procedures. However, achieving a perfect fit at the gum line with stock abutments remains a challenge.

.

..

Standard abutments with different base heights (variants with gingival heights from 1 to 5 mm available)

- The creation of a custom abutment offers the flexibility to adjust the abutment’s height to facilitate easy cement removal and to accommodate variations in gingival levels on the buccal and lingual sides, enhancing the aesthetic outcome. Initially, castable individual abutments were crafted manually due to the absence of CAD/CAM technology. The dental technician would sculpt a prototype from wax and ash-free plastic, which was then cast in metal.

The base for the castable abutment, typically composed of precious metal alloys like gold-platinum, was costly, reflecting the high prices of precious metals at the time. Despite this, such alloys were the only materials suitable for fusing to the custom abutment body.

Subsequently, cobalt-chromium alloys became available, but precious metal alloys remained the preferred standard. The technician shaped the desired profile and volume of the abutment using plastic and wax. A fire-resistant mold made of special clay encased the wax model. Molten metal was then poured into the mold, causing the wax or ash-free plastic to evaporate and be replaced by the metal, resulting in a unique abutment. This abutment was then refined, fitted into a jaw model, and used to form a crown.

As time progressed, despite the longevity of works from the early 2000s using such abutments, the use of precious alloys by practicing dentists has declined due to their prohibitive cost. Consequently, clinicians have adapted to working with stock abutments, while researchers have continued to explore and test new concepts. Historically, cement fixation was regarded as the benchmark for quality.

And everything would be fine if it weren’t for the unhealthy hype about the fact that cement-fixed restorations have a lot of biological complications, for example, peri-implantitis.

And it all started with a work published in 2012.

The research team conducted an extensive analysis of their active practice and observed a notable pattern: biological complications, such as peri-implantitis, were more prevalent in cement-retained crowns compared to screw-retained ones.

Upon further investigation, they revisited a substantial number of their patients for re-examination. During these follow-ups, they discovered that even in the absence of biological changes, remnants of cement were present in the peri-implant tissues.

Then the specialists analyzed all this information, including the medical history of each patient at the time of treatment. And they got very interesting conclusions:

“The study suggests that peri-implantitis could be linked to residual cement in the peri-implant tissues, particularly in patients with pre-existing periodontitis.

In patients without a history of periodontitis, residual cement might lead to a milder form of peri-implantitis or might not contribute to infection. Therefore, cement residues are an additional risk factor for the development of chronic peri-implantitis.

Consequently, screw-retained restorations could be a viable alternative for patients with periodontal disease.”

The publication of the 2012 study sparked a significant shift in the perception of cement-retained implant restorations, leading to both justified scrutiny and some unwarranted criticism. Subsequent research, including authoritative studies, corroborated the initial findings, contributing to a growing body of literature on the subject by 2013-14. Among these, Dr. Wittneben’s report presented at the conciliation conference in Bern in 2013 stands out.

Dr. Wittneben’s work is highly regarded for its quality. The findings from her group’s systematic review were instrumental in shaping the recommendations included in the 8th volume of the ITI Treatment Guide – “Biological and technical complications of implant treatment.”

Let’s look at the findings of a systematic review by Dr. Wittneben published in 2014.

“The five-year survival rate for screw-retained restorations is comparable to that of cement-retained restorations.”

The findings align with Dr. Salvi’s 2008 research, indicating that neither fixation method is inherently inferior to the other. However, additional findings were reported:

“The rate of technical complications was significantly higher for cemented restorations.

Fractures or chips of the ceramic were more common in screw-retained restorations, likely due to structural weakening from the screw shaft.

Weakening of abutment fixation occurred more frequently in cemented restorations.

Other technical complications, such as fractures of the abutment, framework, implant, or screw, occurred at similar rates across both types.”

Notably, loosening of the abutment during cemented restoration is a critical complication, as it often necessitates complete restoration replacement. In contrast, screw-retained restorations allow for easy removal and reinstallation after screw adjustments.

However, screw-retained restorations are prone to chipping, which can be attributed to the occlusal holes typically present in these crowns.

The presence of screw channels in screw-retained restorations indeed introduces a structural vulnerability that may lead to more frequent chipping. This is hypothesized to be due to the weakening of the material around the screw channel.

To mitigate this issue, conical screws, such as Rosen screws, have been designed to distribute the load more uniformly, potentially allowing for the omission of titanium sleeves within the restoration. This design could increase the zirconium thickness and decrease the likelihood of chipping and damage to the restoration. However, as of the current writing, there are no comprehensive qualitative studies that quantify the reduction in chipping risk when using conical screws.

Now let’s look at the conclusions on biological complications from the work of Dr. Wittneben.

“The overall rate of biological complications is significantly higher in cement-retained restorations compared to screw-retained ones.

Suppuration and the presence of a fistula were statistically significantly more common in cement-fixed restorations.

Other biological complications such as bone loss greater than 2 mm, peri-implantitis, peri-implant mucositis, recession, and implant loss showed no significant difference between the two fixation types.”

Here are the final conclusions and recommendations for practicing specialists:

“Given the risks associated with cemented restorations, as well as the limited options for reinterventions after definitive cementation, it seems appropriate to recommend and favor screw-retained restorations.”

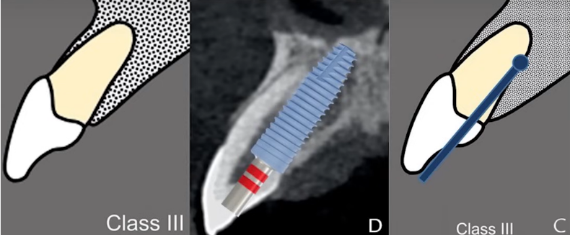

appears that the debate has settled in favor of screw fixation. However, the practical application of screw fixation can be challenging. Here’s the reason: The implant must occupy an optimal position, allowing the screw shaft to exit at the crown’s center with the axis oriented directly towards the opposing teeth. Implementing this in 2014 was a tall order, and even now, with advanced computer models of the jaws and personalized surgical templates, achieving the ideal orthopedic position for an implant is not always feasible. Furthermore, striving for ‘ideal’ placement is occasionally counterproductive. It may be more advantageous to angle the implant and thereby circumvent the need for bone augmentation surgery.

Drilling in the apical direction, parallel to the axis of the tooth and with a displacement of the drill axis palatally – the screw shaft would go to the edge of the tooth, so you need to place a crown with cement fixation

Rigid dogmas declaring one method superior to another can constrain clinicians. Each case requires the resolution of multifactorial issues, and often, medicine resembles an art form. Nonetheless, certain truths are irrefutable. The findings of Dr. Wittneben’s team, as well as the earlier writings of Dr. Linkevicius, stand as facts. Indeed, the contact of cement with the tissues of the gingival margin is a risk factor for complications. However, the presence of cement does not invariably lead to peri-implantitis in every patient with cemented restorations. It suggests that a healthy periodontium may tolerate cement contact without adverse effects.

Patients with a history of periodontitis may experience aggressive peri-implantitis, fistula formation, suppuration, and other complications, even with minimal cement exposure. This concern has given rise to the anti-cement movement. However, the consensus reached at the Bern conciliation conference in 2013 provided clarity.

“High survival rates can be achieved with fixed implant-supported prostheses, either cemented or screw-retained. When choosing the type of prosthesis fixation, failure and complications cannot be avoided.”

After the first reconciling conclusion, the confrontation between cement types is also over:

“Based on the literature reviewed, the type of cement used does not influence the failure rate of cement-retained prostheses.”

A brief note from a practicing dentist: all cements are effective, with the exception of those intended for temporary dentures, commonly known as temporary cements. These can either fail to detach when necessary or disengage at the most inconvenient times. This is particularly problematic when a patient is in another city or abroad, and the restoration becomes dislodged.

The next important statement is:

“Technical complications occurred in both cemented and screw-retained prostheses (estimated annual event rate up to 10%). In the pooled data, cemented prostheses showed a higher rate of technical complications.”

This figure is significant, as it encompasses all types of complications, including ceramic chips and discoloration of the screw shaft seal on the occlusal surface. While most complications are readily resolvable and some do not impede the success of the restoration, it’s noteworthy that even minor deviations from the ideal are considered.

But if we divide complications by type, then:

“Screw-retained dentures have a higher rate of ceramic chipping than cement-retained dentures.”

However, this issue is less pressing today, as metal-ceramics have largely been replaced by solid zirconium prostheses, which are less prone to chipping.

And one more statement based on Dr. Wittneben’s research:

“Biological complications are found in both cemented and screw-retained prostheses (estimated annual event rate up to 7%). Cemented prostheses show a higher rate of fistula formation and suppuration.”

These statistics are somewhat disheartening. Despite some advantages of screw fixation in most comparative analyses, it is not a panacea for avoiding problems and complications. Following this consensus conference, a special publication was released, which includes treatment recommendations that are of particular interest:

Based on this review, it is not possible to issue a universal recommendation for the choice between cement or screw fixation.

Nonetheless, when clinical circumstances permit a choice in the type of prosthesis fixation, certain recommendations may be proposed.

Cement fixation may be recommended:

- For short-length dentures with crown edges at or above the gum level. The procedure for removing cement residues with such parameters does not cause difficulties.

- To improve aesthetics when passing the screw shaft transocclusally or when the implant is incorrectly positioned.

- When an intact occlusal surface is desired. In the case of screw fixation, there will be screw shafts closed with a composite on the chewing surface.

- To reduce initial treatment costs.

- It is further recommended that the clinician understand that procedures involving cemented implant-supported crowns are not simple and must be performed with great care.

Screw fixation may be recommended.

- In conditions of minimal interocclusal space, this is the number one indication from the very beginning of the appearance of screw fixation until now.

- To avoid the possibility of excess cement escaping into the tissue (this is especially important if the edge of the prosthesis is placed submucosally, as it has been shown that it is more difficult to completely remove residual cement from the edges if the edge of the box is located more than 1.5 mm submucosally). Here we would recommend screw fixation if the edge of the crown is below the gum level by more than 0.5 mm, even at 1 mm, it is very difficult to remove residual cement.

- When the possibility of crown revision is important. This is also a very important point; the ability to remove the prosthesis is one of the key advantages of screw fixation.

- In the aesthetic zone to facilitate tissue contouring in the zenith area and in the transition zone (eruption profile).

- For screw fixation, it is recommended that the implant be placed in a prosthetically correct position.

And these are very good recommendations, you can even take a screenshot and return to them from time to time. Despite the fact that 10 years have passed, all these recommendations are still relevant.

Real cases and practical recommendations for both screw and cement fixation

Let’s examine several real clinical cases to discern when the benefits of screw or cement fixation become apparent. It’s important to note that both screw and cement play roles in each fixation type. In cement fixation, the abutment is secured within the implant first, followed by the cementation of the crown or a larger prosthesis supported by multiple abutments.

The challenge with cement fixation lies in the intraoral setting, where removing excess cement can be problematic.

In case of screw fixation, there are two scenarios:

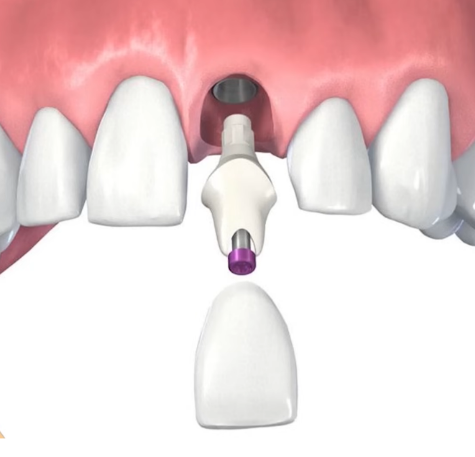

- For single defects, abutments are cemented to the prosthesis externally, away from the oral cavity, allowing for the removal of any cement residues before the assembly is attached to the implant.

2. For multiple restorations, specialized multi-unit abutments are employed. These are installed post-implant integration and remain in place throughout the lifespan of the prostheses. The prosthesis itself is crafted and affixed at the level of these pre-installed multi-unit abutments. Within such prostheses, special bushings are cemented that interface with the multi-unit abutment. However, it is also feasible to secure the prosthesis without bushings, thereby eliminating the use of cement at any stage. Further details on the restoration of multiple defects will be discussed in the upcoming installment of our series on denture fixation methods.

In dentistry, as in other fields of science, the principle of Occam’s razor applies: the simpler the design, the better. In instances where the abutment and a screw-retained crown form a single unit with an optimal eruption profile, without the need for complex fabrication of individual abutments, the solution is not only simpler but often superior.

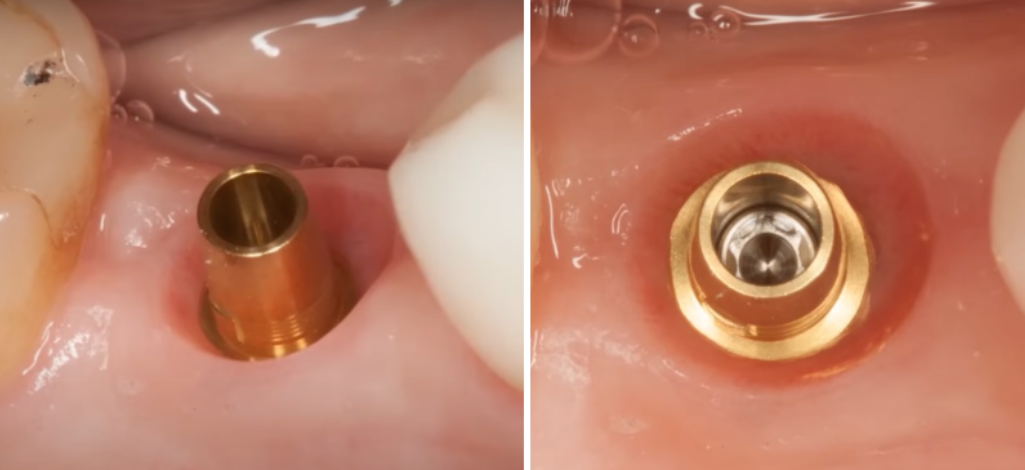

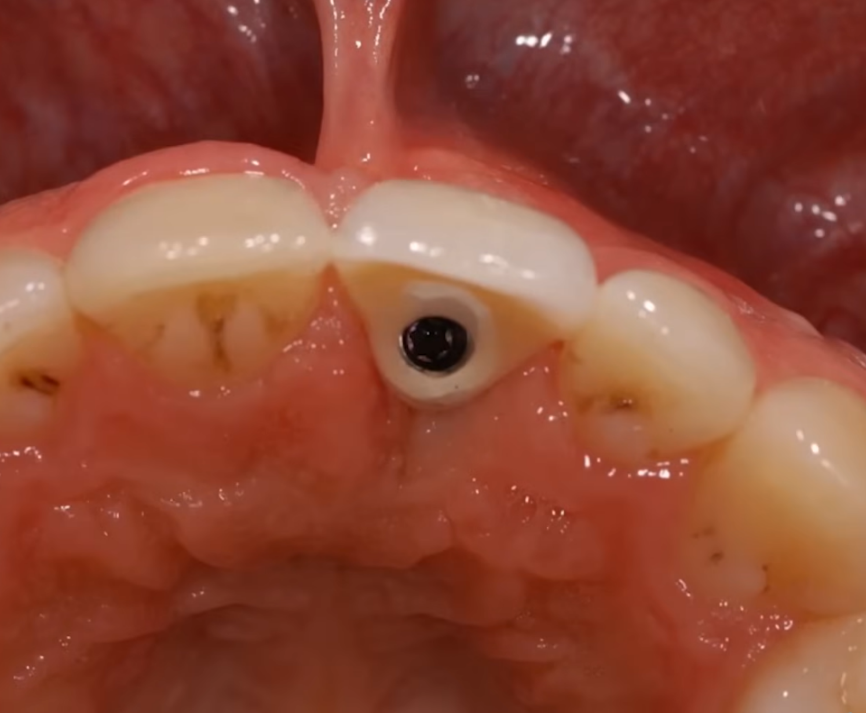

Let’s examine a specific clinical case. The implant has been placed in a very good position, nearly perfect.

Subsequently, a standard abutment was installed, and we observe that the potential bonding line of the crown is quite deep.

Attempting to cement a crown in such a scenario is likely to fail, as excess cement cannot be removed without surgical intervention—a highly undesirable option that would compromise an otherwise healthy gingival collar.

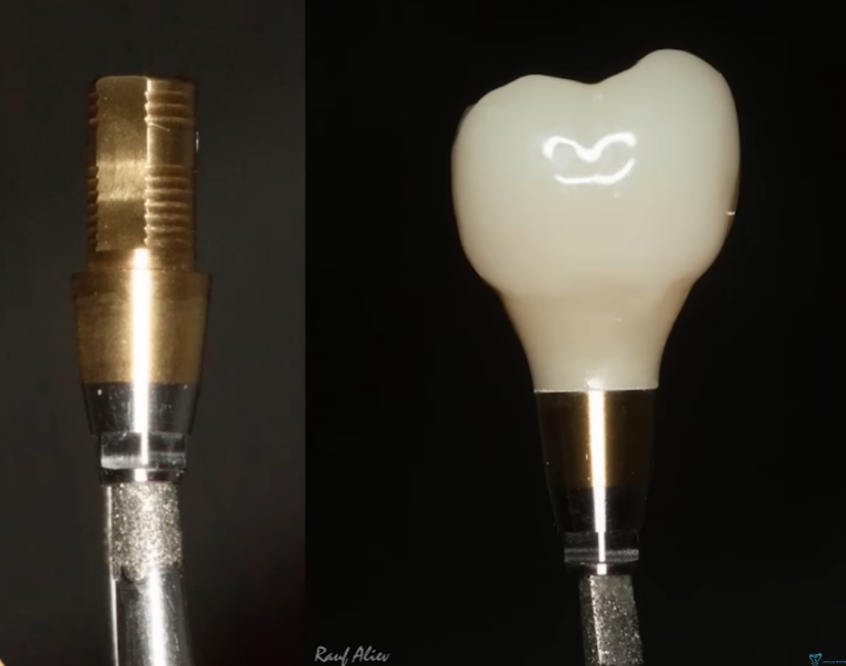

Consequently, the use of a titanium abutment with a digitally milled crown is the appropriate choice here.

The crown is cemented to the abutment either in the laboratory or the clinic, with the essential factor being that this procedure occurs outside the patient’s oral cavity. The distinction in cement fixation lies solely in the location of the cementation process. In a laboratory environment, it is indeed possible to eliminate all excess cement.

In this scenario, the implant is ideally positioned. Screw fixation is simpler and more cost-effective than fabricating a custom abutment and crown for cement fixation.

Now, let’s address a disadvantage of screw fixation: the darkening of the composite at the sites of the screw access channels on the occlusal surface of the prosthesis. The images below illustrate this issue.

Darkening of the screw access channels observed one year after the prosthesis was placed with screw fixation

Is discoloration of the screw access channels a significant complication? For most patients, it poses no issue. If necessary, these composite plugs can be easily replaced during a visit. Occasionally, a composite plug may dislodge, but the patient can have it promptly replaced, leaving the clinic satisfied. Dentists retain the ability to remove and reinstall the restoration, clean or treat the soft tissues, and reposition it. This flexibility is a substantial benefit that outweighs minor issues such as discoloration.

However, it’s important to recognize that some patients, particularly those prone to dysmorphophobia, may acutely reject restorations with even the slightest imperfections. Extreme caution is advised with such patients to avoid the need for redoing restorations and the potential for legal challenges.

Now, let’s consider a less apparent drawback of screw fixation, illustrated by a clinical case involving a deeply placed implant.

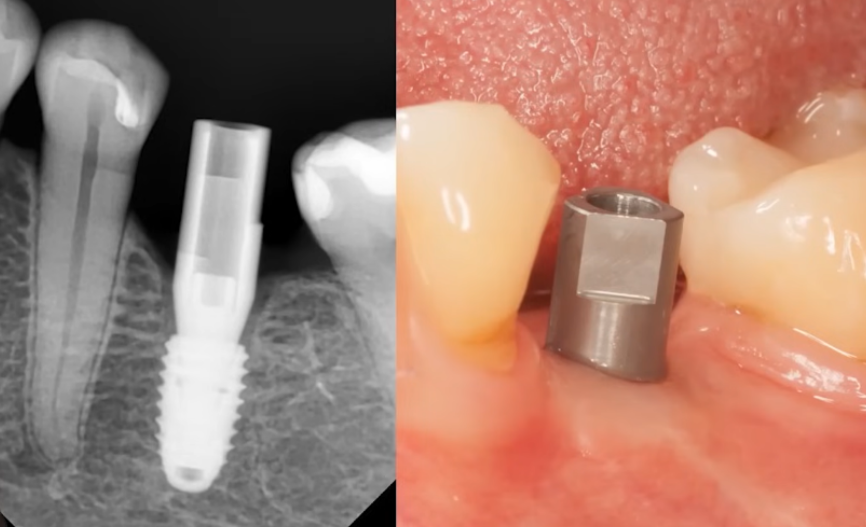

Next, we took a titanium abutment, prepared it, then milled a zirconium dioxide crown, cemented it, and polished the surface that will be in contact with the gums, as recommended in the article discussing the necessity of polishing abutment surfaces.

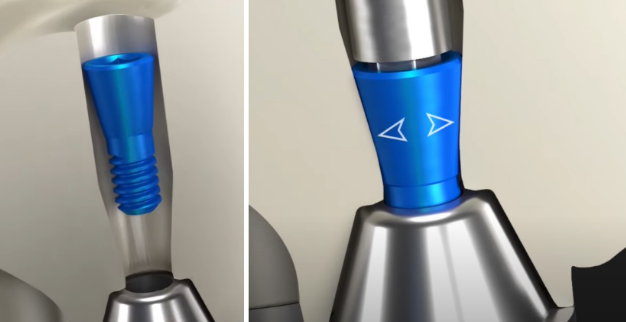

Abutment with anti-rotation features and a crown with an optimal eruption profile for single screw-retained restorations

All preparatory work was executed flawlessly; however, during the crown fixation stage, challenges emerged in positioning the abutment as intended. Approximately 45 minutes elapsed between the two photographs, which is considerable. Additionally, five more detailed photographs were captured at intermediate stages due to the abutment and crown not seating in the desired position.

Challenges arise when the implant platform is deeply set, the crown contacts adjacent teeth, and care must be taken not to harm the gums during installation. These factors collectively complicate the procedure. When selecting a fixation type, these considerations are crucial; cement fixation on an individual abutment might take only 3 to 5 minutes, unlike the hour required in this scenario. For a bridge supported by two implants, positioning the restoration becomes even more complex. Hence, for multiple screw-retained restorations, multi-unit abutments are utilized. They are installed independently and allow for the prosthesis to be easily placed with an ideal passive fit.

Additionally, it’s important to note that screw fixation necessitates precise implant positioning. The illustration below, particularly the lower part, is familiar to professionals and is featured in the ITI guide.

This clearly illustrates the safety zone dividing line (marked by a green stripe) where the implant platform should be positioned. However, this safety zone is actually determined by the preservation of the vestibular bone wall and adequate gum thickness.

Interestingly, it just so happened to be an empirical coincidence that the position of the implant’s center ideally aligns with the successful exit of the screw shaft of the restoration. The position of the implant’s center corresponds to an anatomical feature known as the cingulum. This is a protrusion (tubercle) located on the inside of the central incisors and canines, visible in the photo above. Pronounced in young individuals, these protrusions tend to wear off with age.

The cingulum is the location where the screw shaft should emerge, and thus, the center of the implant. Otherwise, the screw shaft may exit onto the incisal surface or the vestibular portion of the restoration. This would necessitate the production of an individual abutment and a cemented restoration. Currently, it is possible to use angled abutments to direct the screw shaft to the lingual side of the restoration; however, this will be discussed in a subsequent article.

Here, we examine an example of screw fixation on a straight abutment with an optimal orthopedic position of the implant. Yet, there are subtleties to consider as well.

Note the thickness of the crown on the palatal side. The permanent crown, to be made of zirconium dioxide, will be significantly thicker in this area. These nuances must be considered, and patients should be informed accordingly. However, there is no cause for concern. Initially, patients may perceive this tooth as slightly thicker than adjacent ones, but absent any occlusion issues, they will quickly adapt.

Nevertheless, some patients may express concerns. While the dentist’s approach is technically correct, and the implant is ideally positioned as supported by literature and guidelines, there may be instances where a restoration with non-standard proportions is required.

Occasionally, one might consider whether it would be preferable to angle the implant slightly towards the vestibule and fabricate a separate abutment and crown to avoid patient dissatisfaction and remarks.

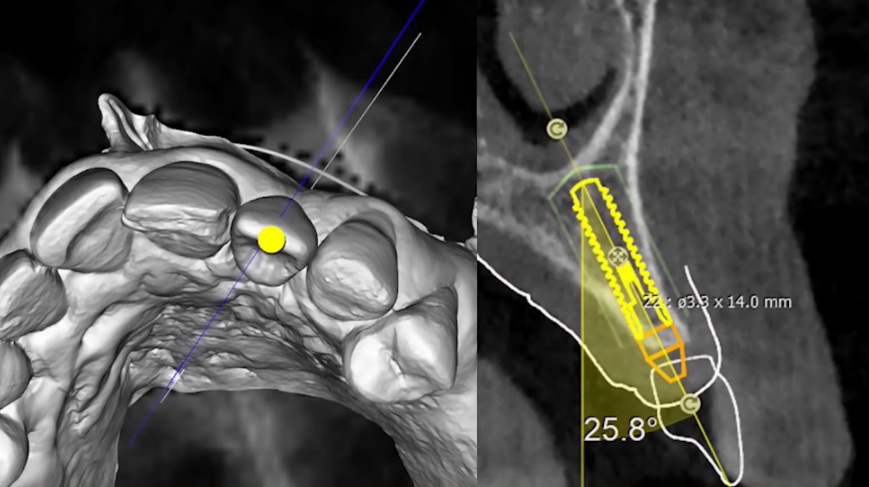

Consequently, we will explore another scenario where the choice was made for an individual abutment and cemented fixation.

The process of planning the implant’s location and the future crown involves considering the patient’s bone tissue condition

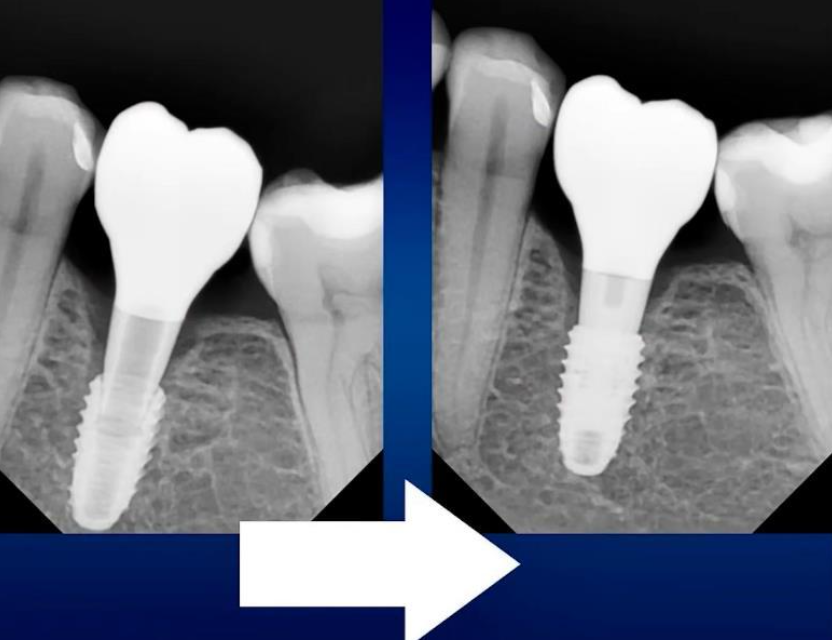

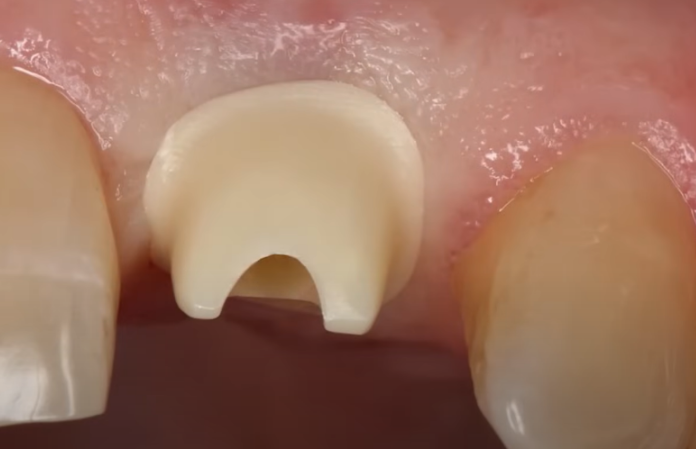

Attempting to reposition the center of the implant for screw fixation would necessitate substantial bone tissue augmentation. In this scenario, the implant’s center extending to the incisal plane is typical. A minor augmentation with a bone graft from the vestibular side proved sufficient for successful implant integration. Subsequently, a custom abutment was fabricated, as depicted in the photo below.

The crown is then cemented to the pre-installed abutment, completing the restoration. Observe the shape of the abutment; the margin of the restoration is supragingival.

The junction between the crown and the abutment is positioned above the gum line, which facilitates the complete removal of any excess cement

The ideal position for cement-retained restorations is such that, in extreme cases, the crown margin can be equigingival.

This principle is fundamental. When a custom abutment is being fabricated, there is no necessity to submerge the crown margin any deeper. Aesthetically, the result will be impeccable. With the crown margin positioned as such, all cement is removed, ensuring a flawlessly maintained restoration.

Even if the abutment’s edge is slightly visible or gum recession occurs, there will be no significant issue. The abutment, crafted from lightweight zirconium dioxide, will have a negligible impact on aesthetics.

Refer to the image below to observe the crown’s fixation. The cement is extruded without entering the subgingival space or the peri-implant tissues. Such precision is highly valuable, justifying the effort invested in creating an individual abutment.

The moment of fixation of the crown – cement is visible, which has protruded from behind the edge of the crown

We can now discern one of the key takeaways of this article. Neither screw nor cement fixation can compensate for a dentist’s lack of expertise. Furthermore, a skilled practitioner achieves excellent outcomes with both methods, selecting the most suitable one by evaluating each clinical case on its own merits.

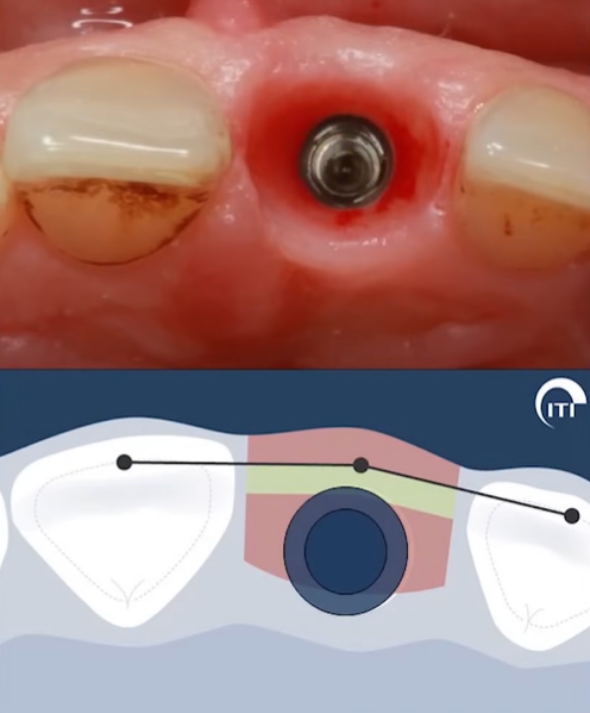

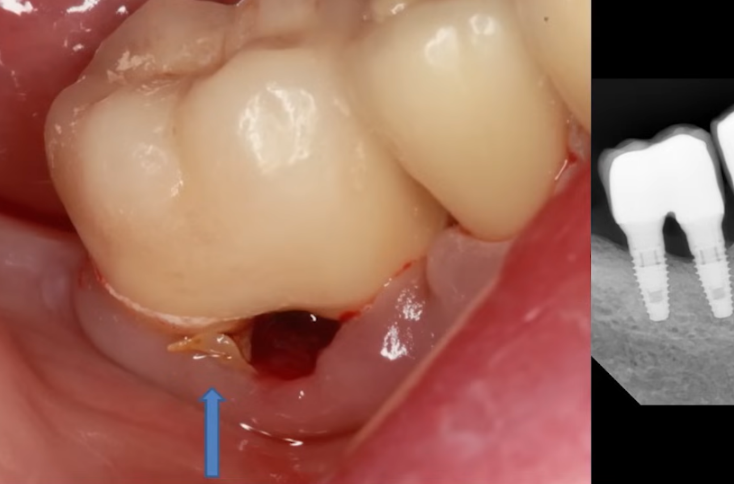

The subsequent case illustrates the long-term consequences of poor decision-making by a dentist.

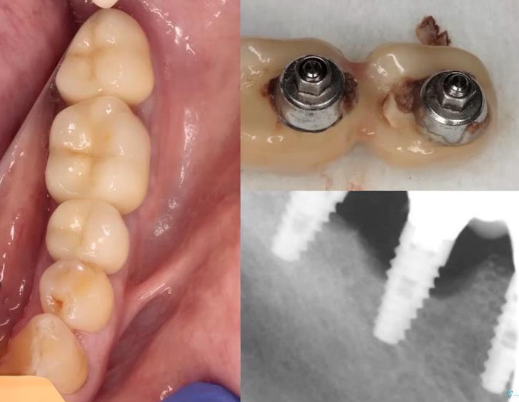

The patient came with inflammation and purulent discharge in the area of the paired restoration. An experienced specialist suspected, even before imaging, that the cause of the inflammation was residual cement beneath the crowns. This suspicion is typical when purulent discharge is localized in such a manner, while the soft tissues around adjacent teeth are relatively healthy.

The suspicion was confirmed; imaging revealed a significant amount of cement beneath the combined crowns. Additionally, it was discovered that the patient had previously suffered from periodontitis, for which they received treatment and had implants and crowns placed at another clinic.

In this instance, the dentist opted to fabricate a single crown for two implants. While this approach is viable, it proved detrimental in this case, particularly given the patient’s history of periodontitis. Removing cement from such a design is fundamentally impractical. The priority should always be the patient’s health, followed by the convenience of prosthesis fabrication and installation. Here, the dentist overlooked essential considerations regarding hygiene and maintenance of the restoration.

To address the issue, a simple procedure to remove the cement was sufficient, resulting in immediate relief for the patient.

We have discussed several clinical cases to illustrate that successful restorations can be achieved with both cement and screw fixation, despite potential complications.

Indeed, screw fixation offers numerous advantages: it’s convenient, straightforward, and cost-effective. Its conditional removability is a significant benefit for most clinical scenarios.

However, we have identified situations where screw fixation may not be the optimal choice. For instance, when the implant platform is exceedingly deep, aligning the crown with the abutment can be laborious. Or, in cases involving anterior teeth restorations. At times, it may be preferable to position the implant in a less orthopedically ideal location to avoid extensive bone augmentation. Yet, this would result in the screw channel emerging at the front of the restoration. To circumvent this, fabricating an individual abutment and a crown for cement fixation is advisable. With CAD/CAM technology, custom abutments can be precisely crafted from zirconia using CNC machining or even 3D printing, eliminating the need for precious metals and casting.

We advocate for the expansion of your skill set to proficiently employ both techniques. In every clinical case, make a judicious decision and prioritize the patient’s well-being.

In our next article, we will delve further into comparing the characteristics and benefits of both fixation types for multiple restorations and examine the fixation process on multi-unit abutments more closely. Stay tuned for future publications.